Agent0028

Inebriated

- Joined

- Nov 12, 2005

- Messages

- 10,758

- Reaction score

- 1

Dang these pics are awesome. I'm tempted, soooo tempted. This piece is growing on me the more I look at it.

Give in to the temptation. You'll be happy you did.

Dang these pics are awesome. I'm tempted, soooo tempted. This piece is growing on me the more I look at it.

Terrific reviews and piccies everyone

I have added them to the Review section so there is easy access to them, so you can view at your leisure:

https://www.sideshowcollectors.com/forums/showthread.php?t=65039

x

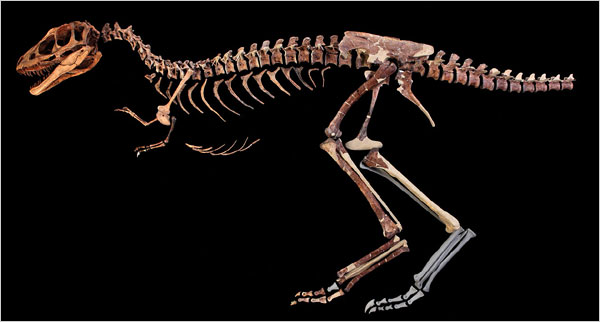

Hey Scar, I'm having a small debate with a friend about the flexibility of tyrannosaur tails. Nerdy, no? But I figured I'd ask you, how much do we know about the rigidity of this creature's tail, particularly toward the end? This statue obviously has some good curly action, but it's not supposed to be as rigid as a dromaeosaur's tail, of course. Any idea what the current line of thought might be?

Oh, and in related news...

Oh Em Gee? Who could this be?

Oh, and in related news...

Oh Em Gee? Who could this be?

Interesting, thanks. I remember hearing about Raptorex, and seeing that reconstruction by... who was it, Marshall? Anyway, I'll assume you consider the Rex Maquette to be fairly acceptable, at least in its tail. Far more convincing than the JP Rex, though obviously not a fair comparison.

So I've got at least one person who thinks the new piece looks like a Stegosaur. My problem with that is the jawline, as you can see. It extends way back, beyond the eye, whereas modern stegosaur reconstructions lend the animal a powerful cheek for holding ground vegetation, capped off by a powerful beak. So I think we're seeing something else. Pterosaur?

You know it buddyWe can always rely on you as the mod to show Dinosauria some love, Shell!

Hey Scar, I'm having a small debate with a friend about the flexibility of tyrannosaur tails. Nerdy, no?...

Scar said:It's a fine debate, and perhaps extant animals illustrate best. For example, cheetahs today have much more rigid tails than lions. Cheetahs are distance hunters that pursue their prey in prolonged sprints, using their tails as rudders essentially to guide themselves more efficiently in pursuit of prey. Conversely lions are ambush predators that make relatively little use of their supple tails when hunting. Now to take the example to an animal a little closer to the point; large monitor lizards have extremely flexible tails which they don't utilize particularly for hunting; again, these are ambush hunters that needn't be swift-footed in order to obtain their prey considering their tactics

Interesting. I can think of a number of candidates here. Can't wait to see more revealed!

The problem of using extant animals to try and make deductions about a dinosaur's behavior is - and I don't mean to sound glib - extant animals aren't dinosaurs. Cheetahs are cheetahs, and T-rexes are T-rexes. While they're both animals, both animals on Earth, both animals affected by things like gravity... they are distinct creatures, and the differences can't be glossed over. It's a trap I'm familiar with from studying physical anthropology: often you see people - even scientists who should know better! - trying to describe early hominids in terms of how they were like chimpanzees (or some other ape). The problem is that australopithecines weren't chimps, australopithecines were australopithecines... and trying to fill in gaps in your knowledge with extant examples is a shortcut - certainly to instant satisfaction, and rarely real knowledge.

T-rex's (or any other theropod's) tail served a purpose that, off the top of my head, doesn't directly correlate to any existing animal - certainly not in magnitude of function - that being counterbalance, keeping rex from helplessly tipping nose-first into the dirt every time he tried to stand up. If we look at rex with an eye towards form following function, he probably didn't have a very flexible tail because flexibility wouldn't make his tail better for balancing (arguably, flexibility would make it worse: if you're walking a tightrope, do you want a 10-foot rigid pole or a 10-foot long water balloon?).

As Scar pointed out, T-rex probably wasn't the fastest of animals, and of course there are lots who believe he was more of a uberscavenger than hunter, for all sorts of reasons. To me though the most compelling argument that rex was more of a scavenger/ambusher/thief than sprinter is the basic physical peril involved in a creature that big - with virtually no front limbs - running. We're talking basic physics here: if a rex in a full run is just a smidge not as surefooted as it thinks, or steps on some loose gravel, or trips over a log or whatever - the resultant fall could easily cripple or kill the animal: take 6-8 tons of meat and bone, exponentially adjust it by the momentum, and bring it all down on the rex's head, with effectively no forelimbs to slow him down. And all of this ignores the basic question of "how does something that big sneak up on anything?"

So anyway, my feeling is that a rex having a tail it can curl and twirl like a house cat is pretty unlikely. Scar uses the example of cheetahs to point out that rigid tails usually mean rudders for sharp turns while running... though I'd go back to the apples & oranges topic I opened with, pointing out that a cheetah is a quadruped, about 100 pounds, and from an entirely different evolutionary line than a T-rex (which by comparison is a biped and about 14,000 pounds). I'm picturing something closer to an alligator's tail, but even more inflexible (as alligators 1) are also quadrupeds and don't rely on their tails for balance as much as a rex would, and 2) use their tail to swim).

Sorry. In hindsight, that all came off a bit more acrimonious that I intended.

Enter your email address to join: